The past decade has been marked by several unique features that have turned the value style of investing on its head. Sean Markowicz, Strategist at Schroders, explains why this abnormal trend may be coming to an end.

Value investing has a long and illustrious history, championed by none other than Benjamin Graham, the man who arguably invented scientific stock analysis in the 1930s.

The premise is simple: investors tend to overpay for stocks with good news to tell – like growth stocks – and underpay for those with bad – like value stocks. Eventually, though, profits return to their long-term average and the mispricing corrects itself, bringing gains to contrarian investors who have defied conventional wisdom and bought value stocks that have been unfairly marked down.

As well as the value of investments going up and down, it is important to note that investors may not get back the amounts originally invested when investing.

The problem is that, since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), value stocks have endured their worst period of underperformance on record. The normal bounce-back for value just hasn’t happened. So does this “lost decade” mean there has been a permanent shift away from value?

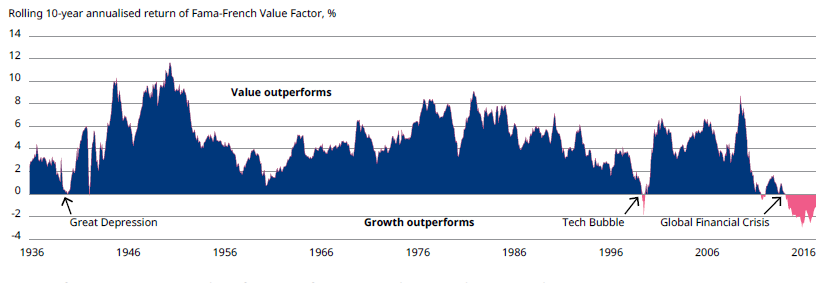

Probably not. For a start, it looks like an anomaly. One measurement of performance developed by two leading academics, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French (see chart), suggests there have been only three significant periods of underperformance for value in the last 90 years: the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Technology Bubble of the 1990s and the post-GFC period of the last 10 years. But the length and depth of the most recent episode is the most extreme on record.

Value has nearly always outperformed growth – until recently

Source: Kenneth French’s Data Library and Schroders. Data from July 1926 to December 2017.

Source: Kenneth French’s Data Library and Schroders. Data from July 1926 to December 2017.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

The last 10 years have been marked by several unique features that have turned value on its head. The most notable has been a prolonged period of slow economic growth following the GFC and accompanying aggressive central bank intervention.

This highly unusual period has radically altered the environment for value stocks. For instance, the abnormally slow recovery in the aftermath of the GFC has meant that the normal “sweet spot” for value, when company earnings rebound after an economic downturn, has been insipid to say the least this time round.

The relative scarcity of earnings growth has also magnified investors’ interest in growth stocks, which are perceived to offer more earnings certainty. This trend has been focused in a handful of tech companies, notably the so-called “FAANG” stocks – Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google (Alphabet). In contrast, value stocks, whose earnings are generally more exposed to economic downturns, have been shunned.

Aggressive central bank intervention has not helped either. This has had the effect of reducing interest rates to historic lows, which has tended to favour growth stocks. Their profits, seen as stretching out into the distant future, are more highly valued by the stock market in these circumstances than when rates are high. Falling interest rates have therefore benefited them far more than value stocks in the recent economic environment.

The combination of minimal growth and low interest rates has fuelled an astounding volume of share buybacks. Since value stocks are typically more cyclical businesses, they tend to have less capacity to return cash to shareholders during bad economic times than growth stocks. In the current economic climate, this has placed value stocks at a significant disadvantage at a time when investors have valued share buybacks.

However, many of these headwinds for value are dying down or reversing. Economic growth is finally picking up, interest rates are rising and buyback activity seems to have peaked.Although nothing is guaranteed, a market rotation in favour of value seems increasingly likely over the coming years.

Furthermore, the valuation difference between value and growth stocks is at its widest level in many years. In the past, differences of this magnitude have heralded significant value outperformance over subsequent years, although past performance is not a guide to future performance.

So big is this gap that our calculations suggest that long-term interest rates would have to fall to zero over the next decade for growth returns to merely equal those from value. If you believe that this scenario is highly unlikely, then betting against value may no longer look like a winning trade.

The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested.

This article has first been published on schroders.com.